About

the Exhibition

ReSOURCE: Art and Resourcefulness in Black Chicago

Since the time of Jean Baptiste Point DuSable, Chicago’s Black culture has been defined by its creative ethos of resourcefulness. Thinking ecologically before there was an environmental movement, generations of Black artists have worked their alchemy to transform simple materials and castoff objects into beautiful art, breathe life into the city’s forgotten corners, and reinvent and reclaim ancestral traditions. The South Side Community Art Center’s ReSOURCE exhibition brings together 40 artists and 70 artworks (including 4 projects commissioned for the exhibition) in partnership with local community gardens and urban farms to tell this story.

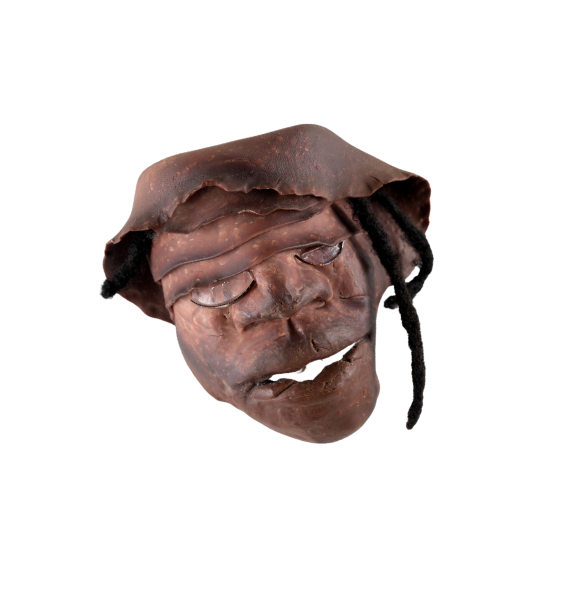

“Alley Stories” explores how the physical elements of Chicago’s urban infrastructure alongside the rhythms of city life function simultaneously as literal and symbolic sources of artistic expression. By utilizing found objects emblematic of urban life—rusted metal, weathered wood, and discarded clothing—the artists in ReSOURCE engage with the complexities of urban existence. In this section of the exhibition, artists address issues of gentrification, displacement, and social inequality’s spatial dimensions, foregrounding the inextricable link between art, the built environment, and broader social and political forces.

Alleys on the South Side of Chicago have always been an important part of Black social and cultural spaces. Essential for deliveries, waste disposal, and other services, Chicago’s network of alleys grew in the early 20th century as a space for working-class communities to socialize and children to find space to play, away from the bustling main streets. In ReSOURCE, multiple artworks have been made from discarded objects found in alleyways, challenging viewers to reconsider their perception of value and beauty.

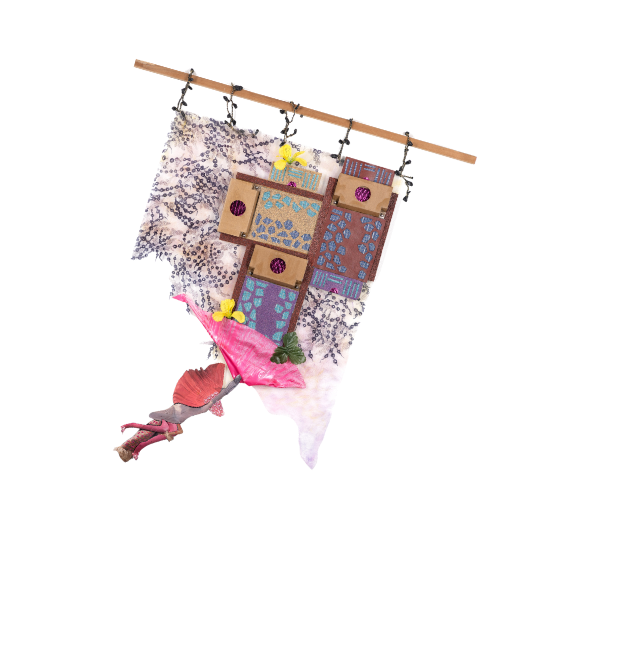

“The Meaning of Materials” invites viewers to see how materials can transcend their mundane origins—or may insist on the meaning to be found in their very materiality. The raw materials of these artworks become potent symbols of resilience, cultural heritage, and social protest. At the heart of ReSOURCE lies a profound exploration of how artists transform materials, revising their original purpose into vessels of meaning, memory, and cultural significance. Within the context of Black artists in Chicago, this transformation takes on a particularly poignant significance, as it reflects the resilience and resourcefulness of a community historically marginalized and overlooked. Through their innovative use of natural materials and found objects, these artists challenge us to rethink our relationship with the material world and to recognize the significance and power inherent within the seemingly ordinary. They advocate for a deeper understanding of our relationship with the natural world and for more mindful approaches to material consumption and production.

“Diasporic Migrations” encapsulates the multifaceted journeys of Black artists in Chicago and their richly layered connections to both physical and metaphysical migrations. This theme pays homage to the resilience, creativity, and cultural heritage of communities whose ancestors undertook the Great Migration from the rural South to urban centers like Chicago in search of economic opportunities and freedom from racial oppression.

Artists in ReSOURCE evoke the memories and experiences of migration, attesting to the enduring spirit of those who traversed vast distances and hardships in search of a better life. “Diasporic Migrations” also encompasses a more metaphysical journey—the intergenerational movement of knowledge and traditions. Whether rooted in African spiritual traditions or the crafting practices of the rural South, migrants carried knowledge with them that became integral to the cultural fabric of Chicago. Through their creative practices, artists celebrate these ancestral legacies to honor the past and seek radical change and healing for the present and future.

View Partner Info and Events

Follow Us

Many prominent artists in Chicago work in an under-recognized tradition of creative genius that “makes do,” recycling materials, repurposing skills, and building on personal and community resources. These practices have a long history on the South Side. From 1940 when the SSCAC was founded by artists like Margaret Burroughs, who scraped together funds for the building’s purchase, to internationally known artists like Theater Gates, Chicago’s Black artists have always made use of what was close to hand: recycled materials, craft skills, and human connections. The Center’s very building, with its New Bauhaus interior design of 1939–40, displays an ethos of resourceful, aesthetically informed repurposing. Famed sculptor Marion Perkins typically sourced his stone for carving from demolition sites in Bronzeville. Using skills brought from the South in the Great Migration, quilters pieced together scraps of fabric into beautiful patterns. An early twentieth-century scrapbook in the Center’s archives displays the common practice of artistically repurposing imagery from advertisements and newspaper clippings. In the mid-twentieth century, “assemblage” artwork was often associated with West Coast Black artists like Betye Saar, Noah Purifoy, David Hammons, and John Outterbridge. Less well known is the fact that Outterbridge spent seven years in Chicago, from 1956 to 1963, working closely (among others) with José Williams, one of the artists in the exhibition.

One of the research discoveries made in the course of planning this exhibition is Mrs. C. Rosenberg Foster. When the Great Depression caused funding cuts for school art classes, Foster devised a way of making art out of trash that she called “trashcraft.” She taught it to her high school students at DuSable High, some of whom went on to be artists and to influence others. She was celebrated nationally and is featured in a 1939 short film called “Unusual Occupations,” which we present here for the run of the exhibition.

Watch

Unusual Occupations, episode 1, 1939.

Written by Gayne Whitman. Narrated by Ken Carpenter. Produced

by Fairbanks & Carlisle. Paramount PIctures.

Segment length 1 minute 58 seconds

Credits

ReSOURCE is part of Art Design Chicago, a citywide collaboration initiated by the Terra Foundation for American Art that highlights the city’s artistic heritage and creative communities.

ReSOURCE is funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art.

Exhibition Staff and Advisors

Exhibition Curators: LaMar R. Gayles, Jr. and Bethany Hill

Terra Foundation Engagement Fellow: Juarez Hawkins

Curatorial and editorial assistant: Rachel Dukes

Exhibition advisor and publication editor: Rebecca Zorach

Publication designer: Aay Preston-Myint

Web design: That’s So Creative

Community Partners: Bronzeville Neighborhood Farm, Earl’s Garden Mae’s Kitchen, First Nations Garden, Grow Greater Englewood, SkyArt, Urban Growers Collective

Special thanks to South Side Community Art Center Executive Director Monique Brinkman-Hill for her unwavering support of this project; to exhibition lenders, including many artists’ personal collections, Bronzeville Historical Society, Karen Davidov, Illinois Institute of Technology Paul V. Galvin Library, Patric McCoy Collection, Beverly Normand Collection, PATRON Gallery, Robert Abbott Sengstacke Art Collection, Dorian Sylvain, Douglas R. Williams Family Collection; to project development advisors Mekazin Alexander, Erika Allen, Tamara Becerra Valdez, Basia Brown, Chelsea Frazier, Seitu Jones, Meida McNeal, Rosalyn Owens, Fawn Pochel, Dejah Powell, Taryn Randle, Anton Seals, and Rashad Shabazz; and to Etiti Ayeni, Lennell Davis, Jada-Amina Harvey, Mandela Hudson, Michael W. Phillips, Jr., Tony Smith, Jacqueline Williams, and Reggie Williamson for their work on the project.

3831 S. Michigan Avenue

Phone: +1.773-373-1026

E-mail: info@sscartcenter.org

Quick Links

- Volunteer

- Become A Member

- News

- Terms & Conditions

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest news and updates from SSCAC.

Copyright © SSCAC South Side Art Center. All rights reserved | Website by That’s So Creative, LLC