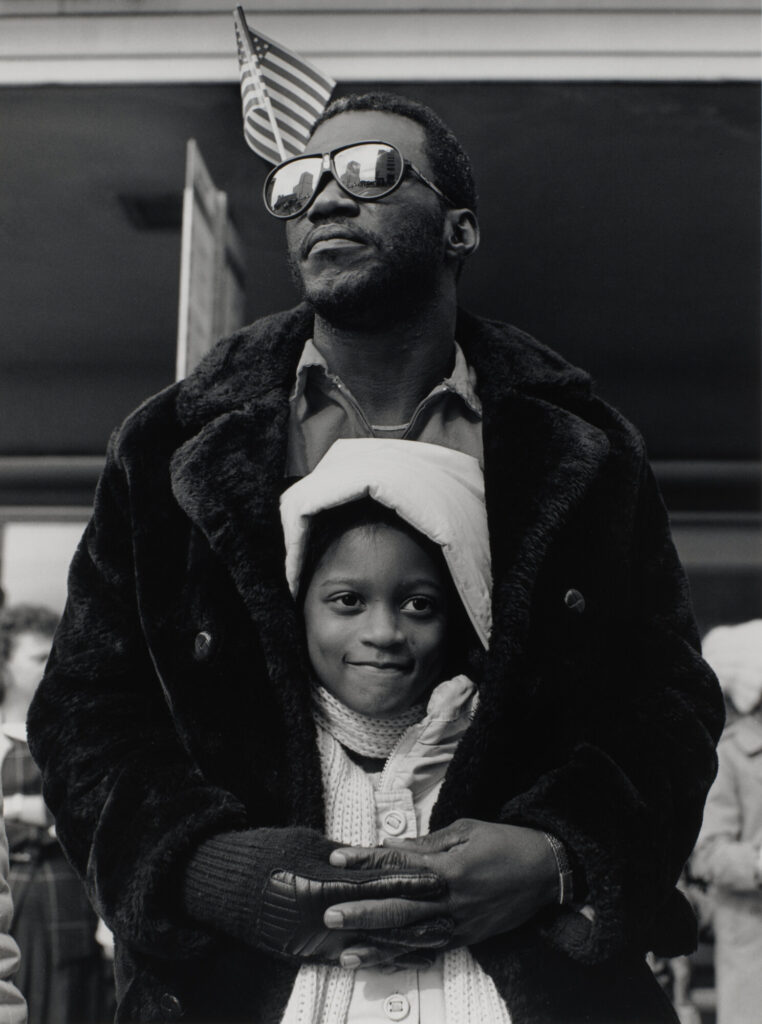

Image by Earlie Hudnall Jr., The Guardian, 1991, silver gelatin print, Collection of The Grace Museum, Museum Purchase with Funds from Alice and Bill Wright

REGISTER HERE!

Emmy-award winning cinematographer and photographer, John Simmons, ASC, and prolific photographer Earlie Hudnall, Jr., sit down with moderator and photographer April Frazier to share with a global audience their successes, challenges, how they overcame obstacles and to share parts of their life work.

The Artists Talk Series is a program of the Darryl Chappell Foundation focused on providing a platform for artists to share their work with a global audience of artists, patrons and an interested public – at no charge. The Artists Talk provides a virtual platform for emerging and established artists to not only share their work experiences, but obstacles along their path and how they were able to confront and overcome challenges. Artists also depict their most recent work, highlighting the trajectory of their path and art practices.

Last, there is a moderated question & answer segment where the audience asks questions either through live zoom audio questions or via chat feature on Zoom or on YouTube. Artists Talk Series are live streamed via YouTube and Zoom and a recording is posted to the Foundation’s YouTube channel within one week of airing live.