ReSOURCE

Artists

travis

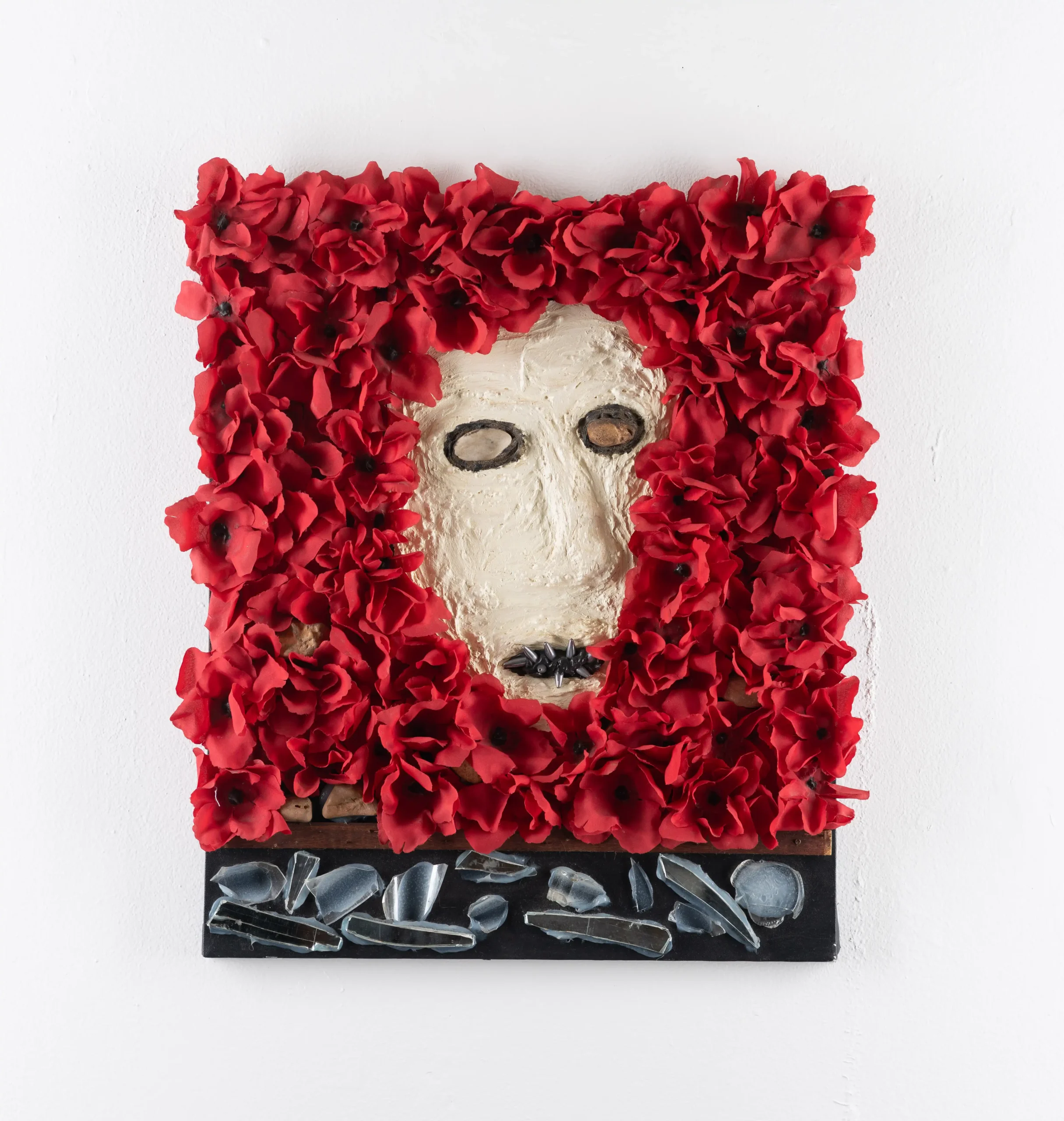

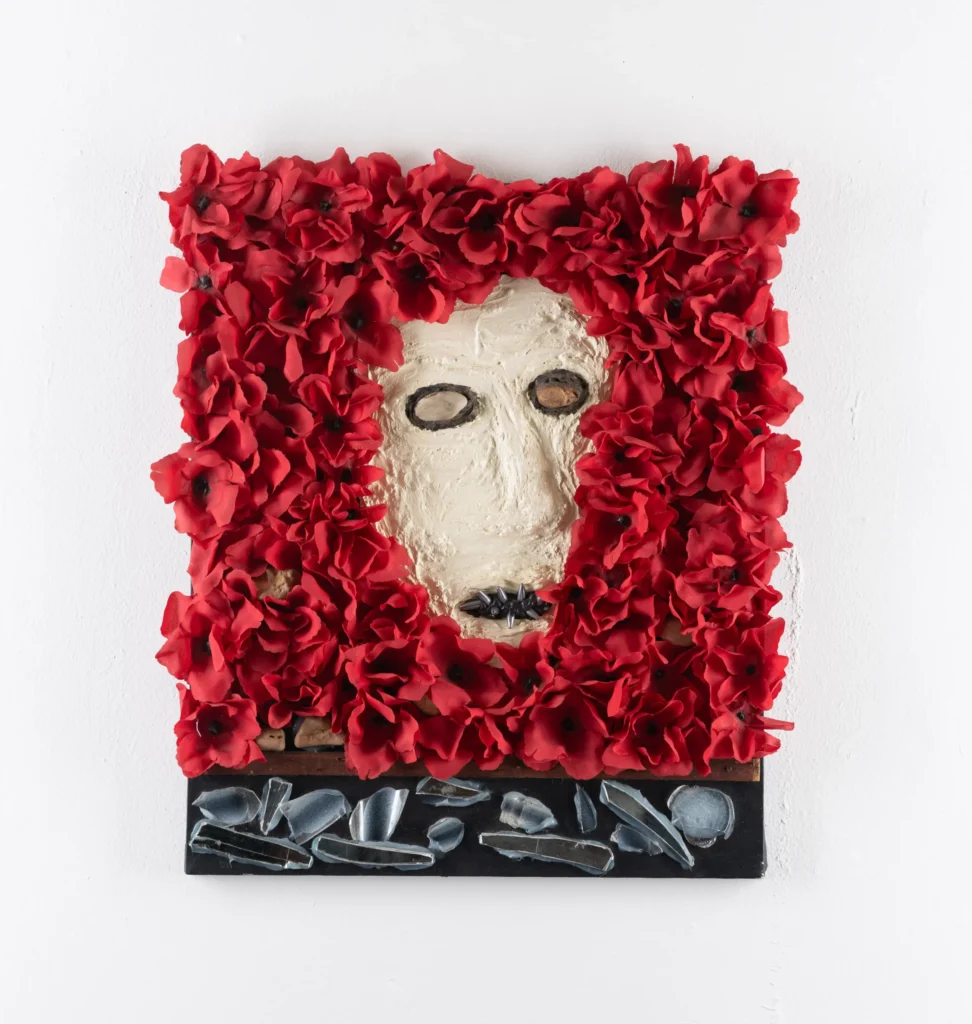

travis (b. 1946) grew up in Itawamba County, Mississippi, where he was born, before moving to Ohio and eventually settling in Chicago. Prior to beginning his academic journey at Northwestern University, where he received his BS in 1990 and an MA in 1993 in Art and Performance, travis served in the US Navy from 1963-1969. He later joined the Chicago chapter of the American Veterans for Equal Rights, an organization that supports the equal treatment of LGBTQIA veterans, and served as both the Vice President and Treasurer for 10 years. His practice spans calligraphy, drawing, painting, sound, live art / performance art, and design, specifically shotgun shack vernacular architecture. His practice springs from a performative approach to race, gendered space, and colonial objectification with the foundational belief that every Black perspective is “rich and valuable. Period!” With his birthplace of Itawamba County as a focal point of his work, travis understands the role of art to stimulate creativity,

imagination, and discovery. Since 1980, travis has performed with a band called ONO (short for onomatopoeia), using traditional instruments as well as detritus, metal, and broken street glass as percussion instruments. He dually leverages these materials in his visual practice and also incorporates found objects from specific locations to highlight the “Black environment” that he is exploring in his work.